TANNIER Eric

- IXXI, INRIA, Lyon, France

- Agricultural Science, Combinatorics, Computational complexity, Design and analysis of algorithms, Evolutionary Biology, Graph theory

- recommender

Recommendations: 2

Reviews: 0

Recommendations: 2

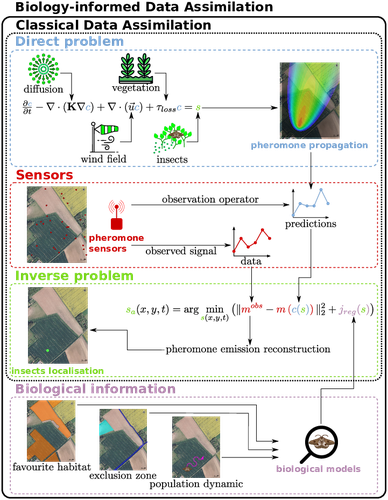

Biology-Informed inverse problems for insect pests detection using pheromone sensors

Towards accurate inference of insect presence landscapes from pheromone sensor networks

Recommended by Eric Tannier based on reviews by Angelo Iollo and 1 anonymous reviewerInsecticides are used to control crop pests and prevent severe crop losses. They are also a major cause of the current decline in biodiversity, contribute to climate change, and pollute soil and water, with consequences for human and environmental health [1]. The rationale behind the work of Malou et al [2] is that some pesticide application protocols can be improved by a better knowledge of the insects, their biology, their ecology and their real-time infestation dynamics in the fields. Thanks to a network of pheromone sensors and a mathematical method to derive the spatio-temporal distribution of pest populations from the signals, it is theoretically possible to adjust the time, dose and area of treatment and to use less pesticide with greater efficiency than an uninformed protocol.

Malou et al [2] focus on the mathematical problem, recognising that its real role in pest control would require work on its implementation and on a benefit-harm analysis. The problem is an "inverse problem" [3] in that it consists of inferring the presence of insects from the trail left by the pheromones, given a model of pheromone diffusion by insects. The main contribution of this work is the formulation and comparison of different regularisation terms in the optimisation inference scheme, in order to guide the optimisation by biological knowledge of specific pests, such as some parameters of population dynamics.

The accuracy and precision of the results are tested and compared on a simple toy example to test the ability of the model and algorithm to detect the source of the pheromones and the efficiency of the data assimilation principle. A further simulation is then carried out on a real plot with realistic parameters and rules based on knowledge of a maize pest. A repositioning of the sensors (informed by the results from the initial positions) is carried out during the test phase to allow better detection.

The work of Malou et al [2] is large, deep and complete. Its includes a detailed study of the numerical solutions of different data assimilation methods, as well as a theoretical reflection on how this work could contribute to agricultural and environmental issues.

References

[1] IPBES (2024). Thematic Assessment Report on the Underlying Causes of Biodiversity Loss and the Determinants of Transformative Change and Options for Achieving the 2050 Vision for Biodiversity of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. O’Brien, K., Garibaldi, L., and Agrawal, A. (eds.). IPBES secretariat, Bonn, Germany. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11382215

[2] Thibault Malou, Nicolas Parisey, Katarzyna Adamczyk-Chauvat, Elisabeta Vergu, Béatrice Laroche, Paul-Andre Calatayud, Philippe Lucas, Simon Labarthe (2025) Biology-Informed inverse problems for insect pests detection using pheromone sensors. HAL, ver.2 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Math Comp Biol https://hal.inrae.fr/hal-04572831v2

[3] Isakov V (2017). Inverse Problems for Partial Differential Equations. Vol. 127. Applied Mathematical Sciences. Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-51658-5.

A workflow for processing global datasets: application to intercropping

Collecting, assembling and sharing data in crop sciences

Recommended by Eric Tannier based on reviews by Christine Dillmann and 2 anonymous reviewersIt is often the case that scientific knowledge exists but is scattered across numerous experimental studies. Because of this dispersion in different formats, it remains difficult to access, extract, reproduce, confirm or generalise. This is the case in crop science, where Mahmoud et al [1] propose to collect and assemble data from numerous field experiments on intercropping.

It happens that the construction of the global dataset requires a lot of time, attention and a well thought-out method, inspired by the literature on data science [2] and adapted to the specificities of crop science. This activity also leads to new possibilities that were not available in individual datasets, such as the detection of full factorial designs using graph theory tools developed on top of the global dataset.

The study by Mahmoud et al [1] has thus multiple dimensions:

- The description of the solutions given to this data assembly challenge.

- The illustration of the usefulness of such procedure in a case study of 37 field experiments on cereal-legume associations. The dataset is publicly available [3], while some results obtained from it have been independently published elsewhere [e.g. 4].

- The description of an algorithm able to detect complete factorial designs.

- An informed discussion of the merits of global datasets compared to alternatives, in particular meta-analyses

- A documented reflection on scientific practices in the era of big data, guided by the principles of open science.

I was particularly interested in the promotion of the FAIR principles, perhaps used a little too uncritically in my view, as an obvious solution to data sharing. On the one hand, I am admiring and grateful for the availability of these data, some of which have never been published, nor associated with published results. This approach is likely to unearth buried treasures. On the other hand, I can understand the reluctance of some data producers to commit to total, definitive sharing, facilitating automatic reading, without having thought about a certain reciprocity on the part of users and use by artificial intelligence. Reciprocity in terms of recognition, as is discussed by Mahmoud et al [1], but also in terms of contribution to the commons [5] or reading conditions for machine learning.

But this is another subject, to be dealt with in the years to come, and for which, perhaps, the contribution recommended here will be enlightening.

References

[1] Mahmoud R., Casadebaig P., Hilgert N., Gaudio N. A workflow for processing global datasets: application to intercropping. 2024. ⟨hal-04145269v2⟩ ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Mathematical and Computational Biology. https://hal.science/hal-04145269

[2] Wickham, H. 2014. Tidy data. Journal of Statistical Software 59(10) https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v059.i10

[3] Gaudio, N., R. Mahmoud, L. Bedoussac, E. Justes, E.-P. Journet, et al. 2023. A global dataset gathering 37 field experiments involving cereal-legume intercrops and their corresponding sole crops. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8081577

[4] Mahmoud, R., Casadebaig, P., Hilgert, N. et al. Species choice and N fertilization influence yield gains through complementarity and selection effects in cereal-legume intercrops. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 42, 12 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-022-00754-y

[5] Bernault, C. « Licences réciproques » et droit d'auteur : l'économie collaborative au service des biens communs ?. Mélanges en l'honneur de François Collart Dutilleul, Dalloz, pp.91-102, 2017, 978-2-247-17057-9. https://shs.hal.science/halshs-01562241